Part 5

Part 5When I woke up I was already walking inside of an old institutional building, a hall of doorways with transoms evenly spaced on both sides, and Diedre was at my side, pushing me along from the back of my arm. We were in a hallway adjacent to Death Row in the state penitentiary. I was surprised that no one was there to stop us, but Diedre’s momentum kept us moving right into one of the rooms. It was like a classroom in the oldest building at my high school, dirty green walls with darkly over-stained wood trim around everything from the dusty hardwood floors to the high water-stained ceiling. All that was missing was a chalkboard. “Diedre,” I said, “our moms?”

“Asleep,” she said. “Don’t worry. I left the AC on.”

Immediately inside the door I recognized the prison electric chair from what I’d seen on TV, but it was much smaller than I had envisioned. The cleaning people, all of them old and black, were in the process of taking it apart, producing things in their pink wrinkled palms for us to inspect. Some copper plates had been removed, and an old woman in a kerchief held one up to me. It was just a little bigger than her outstretched hand. I laid my hand on it, and where I made contact it was cool to the touch for just a moment before it reached body temperature. She held it silently, never looking into my face. The workers all seemed cowed by our presence, tentatively presenting the small parts in their calloused hands to Diedre and me before wiping them with rags and returning them to the chair. She took back the copper plate and wiped it free of my handprint, and before she laid it on the chair’s thick oak arm she showed me that it was clean. It was as though she and the others believed Diedre and I belonged there.

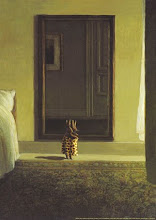

At the far end of the room, two skeletons were sitting upright on a church pew. Their postures were like riders waiting at a bus stop, aloof and unaware of one another. The skeletons weren’t as pristine as the one I’d seen in science class. Some flecks of flesh were still attached to the bones. As we moved farther into the room, the chair cleaners ignored us. Next to the church pew, a box was piled up with miscellaneous bones, disconnected ribs sitting on top, scraped clean of most of their tissue. I glanced around but did not see anyone scraping bones. Tucked between the box and the pew was a lone skull, one that looked more like an ape’s than a human’s, like the skull of a prehistoric man. I knelt down to it and saw something familiar about the shape of its empty eye sockets. This must be Sid, I thought. Cro-Magnon man, we used to call him. Waiting for his bones to be reassembled to make a skeleton like the others that had been seated on the pew.

So there had been three executions, I guessed, Tim, Sid, and some guy I didn’t know, and if I’d guessed right about the skull being Sid, then one of the two skeletons on the church pew must be Tim. Tim and Sid, neither particularly good students, were both going to spend eternity as props in some classroom.

Diedre was examining something that looked like an intact spine. The snake-shaped thing was in a box on a low square table and had the most flesh still attached to it of all the specimens lying around. The fresh tissue was pink and glistening, but it showed signs of severe trauma, red and purple splotches and scorches like a bruised gum. Diedre was leaning down so close to the spine that her shirt sleeve was brushing against it, becoming wet in the surrounding fluid. I was disgusted, almost crying. Clearly someone had died in agony only a short time ago. Diedre had a spinal birth defect, a deformed vertebra she once told me, that caused her chronic pain. She was probably examining the disembodied vertebrae with her own in mind, performing her own personal autopsy. It might not be Sid, I thought. It might be from the corpse of the guy I didn’t know about until we arrived in this room. The stranger seemed to exist to diminish my horror for the same reason that one gun in a firing squad is always loaded with blanks.

“Poor old Sid,” I said, tearing up, “poor old Sid,” just like I was eulogizing a beloved pet. He was a classmate, but he had never been my friend. Now he was dead and Tim was dead, too. Tim’s bones sat on that church pew just like he was ready to start shooting the shit with the stranger, looking right through me from the bench outside the school cafeteria, waiting for Kay Bradley to finish her lunch and come outside. His death already seemed old to me, and I accepted it because it was acceptable. But dear God, for some reason I just couldn’t get over poor Sid.

To be continued…