At first I couldn’t understand why Frank would have his eye on me with someone like Dee around, but little by little I observed that men did not look at Dee the way I would have expected them to. She had something wrong with her back that caused her to limp. It didn’t seem to cause her much pain, but I could tell that she had altered all of her clothing to help hide the fact that one hip was a little higher than the other. In spite of her classically beautiful face and perfect hair, she must have looked like damaged goods to the men who came in the bar. I asked Frank once, didn’t he think Dee was beautiful, and he said he didn’t know. He said she was a good waitress, but it just hurt to look at her.

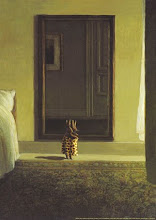

As for me, I tried not to think about the attention I got from the bar customers. The roadhouse had regulars, men and women, but it was so far from town that the majority of the patrons were one-timers, mostly men, truckers and such on their way to somewhere. If I wanted good tips I had to talk nice to them and dress in a manner that would give them a little hope, but hope was all they got. If Frank saw a customer looking at any part of me except my face, the white towel would get cranked down harder and faster into the glasses, and he would tell me to be careful. Under Frank’s watch, Dee and I never had much trouble. After closing and before he did the books each night, Frank would make sure that we got to our cars safely on our way home, in our opposite directions. Soon after that started, I started staying until Frank finished up, and soon after that, I started following him home in my car, but this time he knew I was driving right behind him. He invited me there. I walked in his bedroom. I saw my reflection on the inside of the window as my old self hiding outside, waiting to watch us make love for the first time, and I made Frank pull down the shades.