photo by Michele Guieu

photo by Michele Guieu

Evelyn met Ricky Ford Alton four years ago on the set of the movie that was being made from her first novel, the one that she had based more or less on her own life. He was cast as the English professor who beat her viciously at his loft in downtown L.A. She was twenty when the real incident occurred. As she wrote about it in the novel and in the subsequent screen play, the professor, having hit a dry spell in his own writing career, beat the living shit out of her in a fit of envy because the art came to her so effortlessly and was flowing through her, as though to drown him in his parched river bed of silence, like a flash flood through a canyon. The scene was difficult for her to watch during the filming because she had made it too real, his rage and brutality that had almost killed her, the fact that he left her lying in her own blood on the floor of the loft in no light but that of a strange vermilion dusk, and that she lay there sobbing all night for someone she called Bobby to please come and help her until the professor had the good manners to come back the next morning and call an ambulance for her.

In the novel and screenplay, Bobby was the ghost of an older brother that had died, but she confessed on the set that she was an only child, she had made him up. That night, as they were leaving the studio, Ricky Ford was walking beside her. "So who was the real Bobby, then?" he asked. She forced a knowing smile and kept walking. She wanted to pass it off as some sort of private joke, to push him aside like a gate in her path, but he wouldn’t let her. "I’m serious, it would help me to know," he said.

"He was an imaginary friend," she said and tittered in that superior tone he would come to recognize as the sign that he had found some great subcutaneous truth. She wanted to walk off alone, but she made the mistake off looking back at his face. He was mouthing the word "don’t", she thought, although she couldn’t hear him.

"Don’t what?" she said, spitting both the t’s.

"Don’t go through this alone, Evelyn. Whatever horrible thing is being dredged up for you, let somebody…I don’t know…Let somebody in…Just talk about it. Talk to me." On the set, he acted brilliantly. He shot her glances between takes, glances encoded with deep admiration, seeking her approval, wondering if he was anywhere near the truth as only she would know it, but she knew that he didn’t need her advice to act the part. Out here, however, it appeared that he had no skill at all, no idea what he was doing. He held his hands out, palms up, in a gesture of helplessness. The edges of his body were illuminated by a security light high overhead behind him, and his face was in shadow. She felt the light relentlessly revealing every crease of her own face as his shaded eyes pleaded with her, teach me, Evelyn, teach me to feel what I only know how to act.

“Since when do you read Atlantic anyway?” she asked him. They were half way up Haleakala in the Jeep he had rented.

“Matthew reads it all the time. He showed me your poem. Then he showed itto the rest of the cast and crew.” Matthew was the director of the film that had just wrapped on the aircraft carrier.

“That raises my opinion of Matthew a notch. I wasn’t all that sure he could read. He’s never been able to understand my scripts…”

“Now, now,” he said. “We want to keep rising stars like Matthew as our friends.”

“Anyway, I didn’t have another poem to send them when they asked. I haven’t written much lately that I’m satisfied with.”

“Well that’s perfectly understandable given the circumstances.” He kept his eyes fixed on the winding road ahead, but she watched his roving irises through the side of his Raybans. “You can cut yourself some slack, Ev. Your mother just died.”

“It goes back before that, unfortunately,” she said and turned to watch the tops of the sugar cane spiraling in the wind. “I thought you would have noticed that the computer was in the closet the last time you were home.”

He’d said bravely that he would meet her at the Maui airport, that he didn’t think anyone would recognize him in his post-aircraft-carrier state, the look being so uncharacteristic for him. The aorport was small, and he could wait for her right on the tarmac, and there he stood, in his khaki shorts and tanned but slightly knocked knees, surrounded by men and women unaware and never expecting to see him, oblivious to the magnitude of his stardom, when she descended the steps of the plane.

“Look at you,” she said coyly, taking hold of the lapels of the flowered rayon shirt he was wearing. “All dressed up like Magnum P.I. or something.” The parts he played always changed him, just long enough for Evelyn to feel like she was cheating on him with the character he had become. The more physical the change, the harder it was for him to shake it off. This time, he was tan and he had worked out before the film until he looked ten years younger and leaner than when he’d played the battering professor. Without saying a word, he pushed the Raybans up on top of his head and tried to kiss her passionately, pulling her off her feet with both arms, until she stiffened. “Wait,” she said, touching the lei around his neck that they were about to crush. “This is lovely.”

“Oh yeah…here…Aloha, baby,’ he said in the cheesy actor voice as he passed it over their heads and onto her shoulders. Then she kissed him hard, the lei crushed between them anyway.

“Does this mean I’m getting ‘lei-ed’?” she asked, in her pissy writer voice, suppressing the superior titter so he wouldn’t know how pleased she was to see him in this fit condition after so long at sea.

“Oh yes…” he said, turning her toward the exit with one arm on her waist. “Yes, it most certainly does.”

He still looked the part, a renegade ex-Navy officer who hijacked an aircraft carrier to the Middle East to make trouble for the lesser-paid actors who were supposed to be the good guys of the U.S. Navy but in reality were making nuclear arms sales to a maniac dictator, but he was laughing under his breath with her again, the old Ricky Ford coming up through the layers of the movie character. As he lifted the Raybans back down to his face, the long gray hair he had grown for the part was pulled out from behind his ears, and he looked even less like himself than before.

It was turning out to be a long drive to the house, way up on the west slope of Haleakala, and the mood hadn’t held, at least not completely. She was dissatisfied with what he had to say about her writing. He was too eager to pin all her anxiety on her mother’s death, she thought. “Perfectly understandable given the circumstances” had become his answer for everything that went wrong with her. Angrily she realized that living with her was probably the easiest it had been for him in over a year, now that he could find an explanation for her moods in one word, grief, even though he knew the explanation was both illogical and inadequate. She turned back to face him. “So did you mean what you said about the film?” she asked. “Are you really ruined?” She thought his eyelids lowered for a second, as though he knew she had asked the question to torture him.

He started to speak, but she wasn’t listening. Watching his lips move from that angle reminded her of being with him in another place. Evelyn went on location with him once to North Carolina in the Great Smoky Mountains, and she convinced her mother to drive the two hundred miles from her home to stay in the same lodge with them for a few days. She was seeing him now that first night at dinner, speaking so charmingly of his two teenage sons, talking while he chewed on a little ball of food wedged in his cheek which wasn’t rude at all because her mother did the same thing. He lapsed into his Southern drawl, something he longed to do more often than he should, telling her mother that he grew up the same distance from this place that Evelyn had but in the opposite direction of her home in North Carolina, two hundred miles deep into Tennessee. Evelyn fell out of the conversation early on, but she didn’t mind. She just sat back and watched him as though she were watching him on screen, especially fond of the way he said words like ‘cook’, as in Cookville, Tennessee, flattening the syllables as though they had no vowels. Evelyn learned enough at those dinners with her mother to know, when she found a framed picture in his home of Ricky Ford at the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, that the woman he had his arm around was his sister and that his brother’s name was somewhere on the wall behind them. “Right here,” he said, pointing through the glass, stroking the back of her neck as she held the frame, “you can just make out his name over my shoulder.” In the photograph, the two of them looked so weary, his sister slightly averting her eyes from the lens, their faces drawn like they had both been crying. Then he told her more about his family than he had told her mother, the poorest family in Cookville, the failed shoe stores they’d owned, the house burning down, the love that healed them, the ones who died young, both parents besides the brother in Vietnam. “We’re really dragging the river tonight,” he said as they were lying in bed, afraid that he had overwhelmed her, but she knew he was smiling in the dark as he said it, and she got lost in his metaphor of the river, imagining each dead body as it rose to the surface had a smile on its bloated face, too, so happy to still be loved and remembered.

“So we’ll wait and see. There are plenty of idiots out there who won’t care how bad it is if they hear there are some big tits in it,” he was saying. The road straightened long enough for him to look at her. “You know what I mean?"

“Yes, unfortunately, I do,” she said. “If that’s your biggest problem it’ll probably be a huge hit.”

“No, actually,” he said, starting to laugh, “I think my biggest problem is that the asshole in charge of continuity forgot to have me wear the same damn shirt for all these consecutive scenes, but Matthew wouldn’t let me do them over. Can you believe, he wouldn’t re-shoot the stupid scenes? It’s going to look like I brought a valet or something to help me do quick changes while I hijack the boat. Like I changed into this other shirt to say three lines.” They turned off the main highway, and the new road skirted a pasture full of beavertail cactus and two black and white cows, as pristine as ceramic cream pitchers. For some reason, the sight of them was enough to make Evelyn laugh until she cried.

The house he had rented was on the high side of a sloped street that could have been in any upscale suburb on the mainland were it not for the view. Below lay the green isthmus and the smaller lobe of West Maui, and beyond, the islands of Lanai and Molokai looked like they were a part of the same emerald coastline. Come on, Evelyn, she told herself, if this place doesn’t inspire something poetic, you’re not made of half the stuff you once thought you were. She lingered at the top of the driveway as he passed, saying over his shoulder, "The first thing I’m going to do is get on the phone and find someone to cut my hair. What’s the name of that guy who used to cut my hair who moved out here?"

A second after he went into the house, she shook his question from her head, hoping to hear the voice she hadn’t heard lately, but nothing happened. She joined Ricky Ford in the kitchen as he flipped open the miniscule phone book. "Dave Bridges, I think," she said. "Rhodes or Bridges, one of those."

He ran his finger down one page of the phone book until he saw the name. "Hey, that’s it," he said. "David Bridges is right here." He took her face in his hands and kissed her, then guided her head to his shoulder, enclosing her back with his arms. She fidgeted a bit to get his hair out of her eyes and then inhaled deeply against his neck, pressing her forehead to his skin, knowing that Ricky Ford could occasionally be a surrogate, a vessel from which she could hear that other man’s voice, hoping a stream of brilliant thoughts would again pass by osmosis to her own less saturated mind.

Dave Bridges only worked out of his house these days, a craftsman-style mansion in the middle of a five acre protea farm, but he had consulted with all the biggest stars in Hollywood when he lived on the mainland. He had a great talent for putting people at ease, evaporating their self-consciousness, that got even the most insecure of them to open up. Once he had them in the palm of his hand, he asked them what they really wanted him to do with their hair. They were invariably so relaxed that they answered as though drugged by sodium pentothal, and he cut their hair the way they told him to. It was that simple.

This morning he had a fire going in his big stone fireplace, and it was having a similar effect on Evelyn. She slipped off his couch and onto the carpet, her legs curled up beneath her, while he cut Ricky Ford’s hair.

“Jet lag catching up with you?” Dave asked as she yawned and lowered her head to the floor.

“Yeah, I guess. I woke up way too early this morning and couldn’t get back to sleep.” At dawn, she stood on the deck, the fog pink from the sun rising behind Haleakala, covering everything up to exactly the level of their street so that the isthmus completely disappeared beneath it. West Maui looked like an island, just the top of the peak visible above the otherwise undisturbed field of clouds. About an hour later, Ricky Ford shuffled onto the deck with a mug of coffee. “I have an irrational urge to try to walk across the clouds to West Maui,” she told him.

“They’ll burn off in an hour and you’ll fall to your death over the Pukalani Country Club,” he said. He leaned back on the chaise and closed his eyes.

“Yeah, but what a way to go, huh?” she said. He didn’t answer. She thought he was disappointed that she had not stayed in bed with him. He had nothing else to say until it was time to go to his appointment.

to be continued..

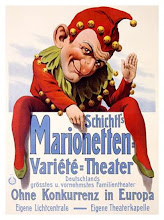

I've been away from the blog for almost 2 months now which is a shame because it seems like I don't read my friends blogs unless I'm keeping up my end of things. I've been really busy prepping for a show at Diversionary Theatre here in San Diego, "As Much As You Can," for which I am designing the set. I created the image you see above (well, actually I adapted it, but you'd never recognize the original) as a possible set piece--it sort of sums up the complexity of a family--a family tree with so many twists and branches that the birds who nest there look as though they can't find one another. I'm neither disappointed nor relieved that this image will not be appearing on the stage--no, I take that back; I was relieved when the director had a clear enough vision of the play to ask me what we were asking the audience to believe this piece was. Was it a painting, or a tree? What did it have to do with the sort of iconic family/life vignettes we had created otherwise? We decided we didn't want to go there. But we both have seen the image of the tree now, if you know what I mean. We shared it, so it wasn't wasted.

I've been away from the blog for almost 2 months now which is a shame because it seems like I don't read my friends blogs unless I'm keeping up my end of things. I've been really busy prepping for a show at Diversionary Theatre here in San Diego, "As Much As You Can," for which I am designing the set. I created the image you see above (well, actually I adapted it, but you'd never recognize the original) as a possible set piece--it sort of sums up the complexity of a family--a family tree with so many twists and branches that the birds who nest there look as though they can't find one another. I'm neither disappointed nor relieved that this image will not be appearing on the stage--no, I take that back; I was relieved when the director had a clear enough vision of the play to ask me what we were asking the audience to believe this piece was. Was it a painting, or a tree? What did it have to do with the sort of iconic family/life vignettes we had created otherwise? We decided we didn't want to go there. But we both have seen the image of the tree now, if you know what I mean. We shared it, so it wasn't wasted.

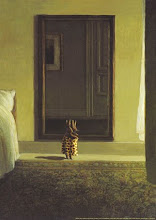

But in the past few weeks, it has dawned on us that we are really getting this:

But in the past few weeks, it has dawned on us that we are really getting this:

Middle-aged middle-class Americans are getting a severe history lesson, a first hand encounter with the kind of class rage that caused 18th century France to erupt in a purging violence that necessitated the invention of the guillotine.

Middle-aged middle-class Americans are getting a severe history lesson, a first hand encounter with the kind of class rage that caused 18th century France to erupt in a purging violence that necessitated the invention of the guillotine. I wish I had a fortune cookie I could still eat, I thought. I trashed the flotsam and jetsam of my lunch and went to the loo. When I came out, I saw that the counter nearest the front window was unoccupied and perfectly clean save one intact cellophane-wrapped fortune cookie. I took it, opened it and ate it on the way to my car. The fortune in the second, edible cookie was this:

I wish I had a fortune cookie I could still eat, I thought. I trashed the flotsam and jetsam of my lunch and went to the loo. When I came out, I saw that the counter nearest the front window was unoccupied and perfectly clean save one intact cellophane-wrapped fortune cookie. I took it, opened it and ate it on the way to my car. The fortune in the second, edible cookie was this:

the outer banks of North Carolina

the outer banks of North Carolina Islay in Scotland

Islay in Scotland

not gaining weight

not gaining weight reading slutty books or Nancy Drew

reading slutty books or Nancy Drew not reading Joyce

not reading Joyce riding around with my uncle who knows all the good stories

riding around with my uncle who knows all the good stories getting the filter removed from my vena cava

getting the filter removed from my vena cava the tour de France

the tour de France reading about the festivals in NME in the aisles of Borders

reading about the festivals in NME in the aisles of Borders