Part 2

Just after their marriage, my mother and father went in search of a nameless cay in the Exuma archipelago where, they had heard, a few people lived who were badly in need of a sense of community, a connection to the Lord. At that time, and still today, none of the islands northwest of Great Exuma had a name except Baraterre which might as well be a part of Great Exuma it is so close. But the cays beyond it are spread out across the Atlantic like the bones of a great dissected spine and are not considered to be inhabited, but only because no one takes the time to see if they are. Descendants of the ‘Indians’ who lived throughout the Caribbean before the European migration swept most of them up as slaves or killed them with Old World diseases are still living in the Exumas, in some cases only one or two families to a cay, living their lives much as their ancestors did with the exception of two things. One is that the children are all gone. They have commuted to the present, transported off to the main island schools for a better education, and they have not come back home. The other is that those who stayed behind were all converted to Christianity. My father learned of this forgotten flock with their church crumbling into the surf from an obscure reference in National Geographic. He used the magazine as his atlas in seminary as he planned his life as a missionary, but unlike some of his classmates, he was not evangelical; he did not advocate proselytizing Christianity to other religions. So the idea of rebuilding the church on the cay was irresistible to him, serving a gathering of ready saved souls that needed a pulpit placed before it. He convinced my mother, a junior Bible college graduate, to marry him and join him on his crusade.

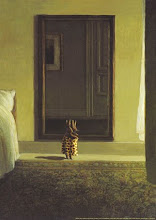

What they found when they got there was an island that had been abandoned long before the church had shrugged its shoulders and collapsed into the sea. The tiny cay was shaped like a melted slice of cheesecake, the graham cracker crust being a magnificent broad cliff a hundred feet high, the melted-down tip a shallow and treacherous point of submerged rocks. At the base of the cliff, the ocean opened up into a deep blue trench that looked like a bruise when viewed from the top of the ravine left by the landslide that had taken the church. Any boat that arrived at the island had to land midway between the two ends, necessitating a short precipitous climb to the habitable surface. Three small houses still stood in a crescent around the site of the church’s demise, but they were overrun with vegetation.

No comments:

Post a Comment