Part 12

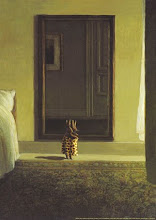

Part 12For a week or so after Frank died, I had one dream over and over again. I would be in a house with immaculate white walls and miles and miles of thick blue carpet. There was furniture, but I could never remember what it looked like. I was wandering this very large house looking for something, I don’t know what, but I knew that if I was to find it, it would have to be inside one of these rooms because outside of every window was the densest green jungle I had ever seen. I woke up one morning after the dream, and something finally occurred to me. It struck me that, in his whole life, Frank had never seen the ocean. Emily was almost eight, and she had never seen one either.

The following month, as soon as Emily’s school let out, we went to Baraterre. Touring around the island the day we arrived, I showed her the sites that represented the beginning of my life. Fat Billy’s was now run by a small Vietnamese woman, and the sight of her made me miss Fat Billy, even though I had never once met him since the age of eleven months. He was a part of that other time that should have just been history to me, but I was always confusing history with memory.

I hired a boat to take us to Church Cay for the day. As Emily and I scrambled up the bluff to the plateau, I watched the boatman reclining with a cigarette in his boat, watching us. “Your father built the shill church, heh?” he had asked me, amused. I wondered if he felt enough ridicule to try to scare us by leaving us stranded. I supposed that my mother had wondered that every day she was here, and she might have sometimes felt the same derision toward my father.

The church was just as I had pictured it at the high end of the island. All its paint had worn off or had been bleached away in the sun, and its bare wood was as gray and tufted as the fur of an animal. It felt like a doll house. Emily tugged on the iron handle of the front door, and the whole structure shook. She pouted and then turned her back on it, running off to explore the ruins of the older houses. I was relieved to have her playing away from the cliff. I stood near the front of the church myself and looked down for the first time at the trench a hundred feet below. Beneath the small crests on the water’s surface, the smoothness of the patch of dark blue surprised me. I knew there was a very old church down there. I pictured its pews, its hymnals, someone’s forgotten Sunday hat. But they had been completely absorbed in the uniformity of that field of blue. Emily hummed happily as she sat braiding leaves next to a grave marker, and it seemed inevitable that the cemetery and all of its contents would be consumed by the trench too. The dead were headed for oblivion, and that made me happy for them. They were in their own vortex, waiting to be dropped out into a strange land for the last time. I decided that I loved the underscaled building that stood before me, the shill church, for its ridiculous appropriateness at being so empty.

Emily was so content playing there that I put off our leaving until I heard the boatman call up to us. On the way back to Baraterre, she sat with one arm around my waist and the other outstretched, her hand cupped to catch the wind. Every few minutes she rushed her hand to her open mouth. She was tasting the air, doing the exact same thing I had taught Jeff to do as a baby on our long Sunday morning car rides to the church where our father would be preaching.

Twelve years have passed since that summer, and now I live in Baraterre. When the men told me that my father’s church had fallen into the ocean, they said that so much of the cliff had eroded that the edge now broke inland right up to the boundary of the old cemetery. I imagine that in a few years, the ancient coffins might come spewing out of the hillside to find their way down onto the rocks below, or if they are lucky, slide right into the trench. The scant human remains will spiral back down to the crude depths of life’s origins, the sea.

This is the story of my life, and I am back where I began. Make something out of it if you can. My story, that is.

The End

the outer banks of North Carolina

the outer banks of North Carolina Islay in Scotland

Islay in Scotland

not gaining weight

not gaining weight reading slutty books or Nancy Drew

reading slutty books or Nancy Drew not reading Joyce

not reading Joyce riding around with my uncle who knows all the good stories

riding around with my uncle who knows all the good stories getting the filter removed from my vena cava

getting the filter removed from my vena cava the tour de France

the tour de France reading about the festivals in NME in the aisles of Borders

reading about the festivals in NME in the aisles of Borders