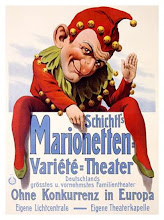

Alan Rickman, an Emmy-worthy performance as a doctor in Something the Lord Made.

I love presenting a brit a day, but I don't want to be dead as a fiction writer. I'm working on a story that has a doctor as one of the central characters--if you read Thursday's post this will probably not surprise you, as I do wax poetic on doctors from time to time--and have sooo little left to do, but I seem to be avoiding it. Don't want it to end? Perhaps because then I have to do something else, start something new, in order not to be....dead as a fiction writer.

Speaking of dead authors, I've returned to the novel I think I love more than any other for a third [more?] reading--Lady Chatterley's Lover. Usually I say that life is too short and the world library is too large to re-read books, but since nothing has surpassed it, I indulge myself again. D. H. Lawrence could not have been born into a society less fit for his genius than early 20th century England. When I read his prose, I often cry, not only for the beauty of it, but for all the missed opportunity and misunderstanding that afflict those who have shunned it without ever reading it. Reputation is such a dangerous, pivotal attribute for an artist. Pivotal because it can turn on a dime.

Here is an excerpt from the Wikipedia about the campaign by his friends to rally against his critics after his death--

D H Lawrence’s friend Catherine Carswell summed up his life in a letter to the periodical Time and Tide published on 16 March 1930. In response to his critics, she claimed:

In the face of formidable initial disadvantages and life-long delicacy, poverty that lasted for three quarters of his life and hostility that survives his death, he did nothing that he did not really want to do, and all that he most wanted to do he did. He went all over the world, he owned a ranch, he lived in the most beautiful corners of Europe, and met whom he wanted to meet and told them that they were wrong and he was right. He painted and made things, and sang, and rode. He wrote something like three dozen books, of which even the worst page dances with life that could be mistaken for no other man's, while the best are admitted, even by those who hate him, to be unsurpassed. Without vices, with most human virtues, the husband of one wife, scrupulously honest, this estimable citizen yet managed to keep free from the shackles of civilization and the cant of literary cliques. He would have laughed lightly and cursed venomously in passing at the solemn owls—each one secretly chained by the leg—who now conduct his inquest. To do his work and lead his life in spite of them took some doing, but he did it, and long after they are forgotten, sensitive and innocent people—if any are left—will turn Lawrence's pages and will know from them what sort of a rare man Lawrence was.

No comments:

Post a Comment